— Northwestern Wales contains multitudes, but the constants are these: wind, rain, sun, sheep, and slate, often in the same afternoon. A few of these are evident on this hillside path outside the tiny village of Penmachno, once a quarry town in the isolated Machno river valley about eight kilometers south of Betws-y-Coed.

Here one of the many steep hillside grazers has hopped up on a slate wall to get a closer look at a visitor coming down into the village.

This region is increasingly popular for bedroom commuters to big cities, but when traveling east-west in the UK and off the main spoke routes, it can take eight hours making connections to get here by public transport. Which it did. Then you have to phone in advance to the bus service for pickup at the scheduled time from the town nearest to Penmachno. Which I did not. Because I am a dunderhead, and I did not know this practice. The next opportunity to call for a scheduled bus was in two days.

The kind pubowner from The Eagles bunkhouse left his Friday bartending to come pick me up himself.

— Fresh prints on the mountain: this pop-up installation on the high road above Penmachno brought together youth and residents in painting and printmaking. Inside the temporary hut hung flyers looking like Tibetan prayer flags evoking local myths and stories as the brisk July wind clattered the boards.

Conductor of ceremonies here is Rhodri Owen, an artist and furniture maker from nearby Ysbyty Ifan village. This spot was the midpoint for roads from the Machno valley to the next, site of a long-vanished inn, and in the surrounds of a bleak, uncomfortable, but effective hideout territory for bandits.

— Penmachno village has maybe three intersections (or four, if you squint). At the corner of High Street and Llewelyn for many years was a derelict photoprinting shop (analog printing + tiny village, so = grim business outlook).

It’s been cleared out and turned into a community gallery and meeting space thanks to volunteerism and a break on rent in exchange for upkeep. In other words, sweat equity. Active residents, the building owners Lindsey and Peter Haveland, a community organizer connected to a local utility and members of the non-profit Clear Village, a SMOTIES partner, got the renovation done. It’s called Oriel Machno.

— On the week I was there Oriel Machno hosted a local Archaeology Day, fielding a steady stream of visitors wanting to talk with Gwynedd Archaeological Trust project scientist Bethan Jones, who lives with her partner and their young child on a National Trust farm up the hill from Penmachno.

Visitors including this (EXTREMELY knowledgeable) teen talked local digs, LIDAR mapping, and Iron Age pottery shards all afternoon. Clear Villager and fine artist Kristin Luke, who has lived in the village since 2017, promoted and organized the event.

— Penmachno has children but they go to school down the road. Here, this old, pretty, and abandoned school building has become site for another local effort: the doors and arched stone entry are beautiful, and the inside? A work in progress. The plan is to make it a larger social hall and community spot, perhaps with small studio spaces for making things and a common room.

Bingo may also be on the agenda, says Sian Rhun (seen here, left, talking over the building with visitors). Rhun’s family tree is for generations firmly rooted in the Machno valley, and she is a fountain of energy.

The Welsh language is widespread, prominent and important to this part of the world.

In Penmachno it’s spoken in the pub and at home and is a key to the place (thought its stalwart shop-owning family has roots in south Asia: the village may be remote, tiny, but does not feel instinctively insular).

Though enduring the same lousy economics as any other media, Welsh-language publications of all kinds are for now still available in easy reach.

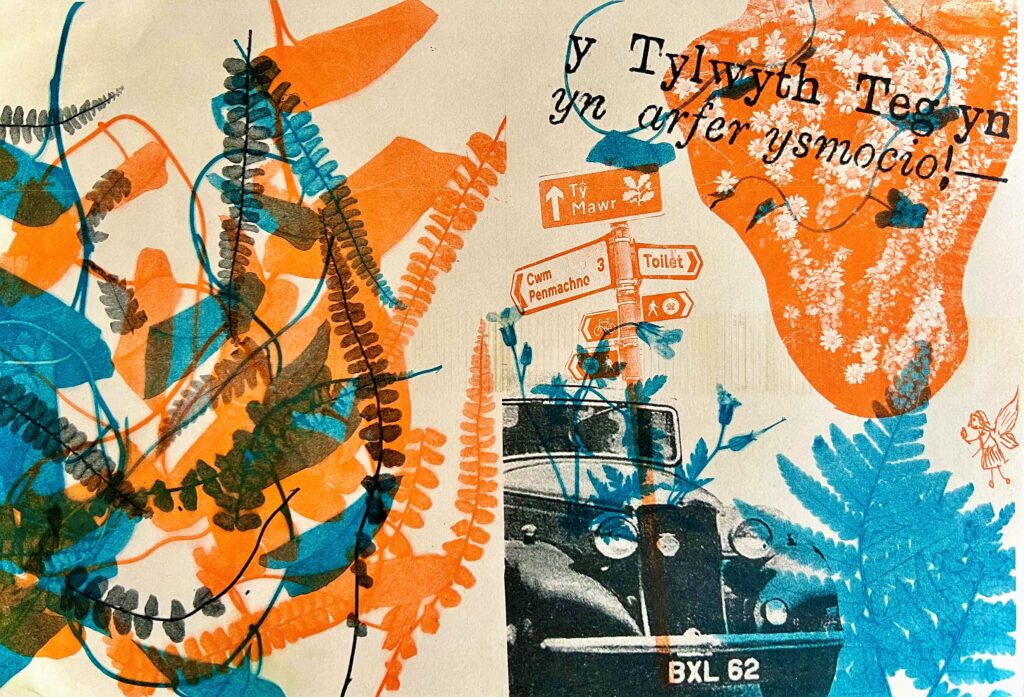

Kristin Luke runs what is certainly the only printmaking workshop for miles around centered on the Risograph, a three-color ink digital duplicator prominent in 80s’-era political and artmaking circles for pamphleteering. Luke travels to meet an ink dealer from Birmingham to refill the Riso drums as needed.

Here she’s showing the ropes to the Risograph to a young aspiring graphic artist…

…who made this print with it, using images, inks, silhouettes of found leaves, and typeface.

— Once up into the high hills and moors above the village it is, essentially, rolling wetlands. The marshy grasses and water produce peat, which has a complicated history: it’s (kind of) a fossil fuel, it’s charred the ceiling of many a hut; it’s a favored flavor in whisky; and it is increasingly viewed as a potential carbon sink, absorbing and trapping greenhouse gasses.

Iago Thomas, a National Trust landscaper and pet expert, showed me around the bogland not far from the spot of the pop-up art hut at the moorland crossroads shown earlier. I did not know how wet it could get in those grasses. With me I only had canvas shoes.

Next time I’ll know better. But I wasn’t going to not go.

— And if you’re in the peatland wondering about your wet feet and your next potentially perilous steps and the next steps for the place: it also pays to look up and around.

Farewell then to Penmachno. In our next post we’ll find water in a much different environment: in the Aegean Sea, from the Cycladic island of Syros.